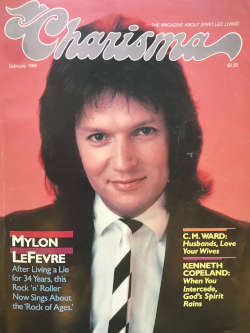

Mylon LeFevre: Using Rock to Reach Christian Youth

Note: This article was written for the February 1985 issue of Charisma Magazine.

A beat reverberates through the dimly lit Mt. Paran Church of God auditorium. Teenagers on the front row are on their feet, clapping and cheering. On stage, members of the rock band wave guitars in the air. Their song concludes in a burst of light and fireworks.

This is no ordinary gospel concert.

A lone figure approaches center stage. He is dressed in flashy red trousers, white knee-high boots, a black shirt and a red jacket. His dark hair falls over his collar.

A lone figure approaches center stage. He is dressed in flashy red trousers, white knee-high boots, a black shirt and a red jacket. His dark hair falls over his collar.

He’s the church’s outreach pastor and one of the congregation’s 24 elders. This is a Monday night outreach in an auditorium of Mt. Paran Church of God’s big Family Life Center complex behind the church’s 7,000-seat auditorium.

He gestures around the darkened auditorium. “I’ve stayed in (ex-Beatle) George Harrison’s house, and his house is bigger than this building,” he says in his slow Atlanta drawl. “It used to be a monastery.”

He pauses.

“Me and Elvis used to get high together. We lived in castles together.” The audience is hushed. Many have heard the testimony before. They know that once the pre-teen LeFevre used to smoke marijuana with band members of his parents’ Southern gospel singing group before he performed traditional favorites about Jesus.

By the time he was in junior high, he was taking drugs regularly before he would come on stage with the Singing LeFevre Family. There he was, the rosy cheeked, cute little boy who did solos of “Jesus Loves Me, Jesus Wants Me for a Sunbeam” and “The B-I-B-L-E.” What few of the adoring adults knew was that he was higher than a kite and laughing at them.

“As a kid, I was a gospel singer who never led anybody to the Lord,” he admits. “I sang about Jesus, but I was gettin’ loaded as a little guy. I was singing ‘Amazing Grace’ and taking acid at the same time.”

He recounts incidents as a youngster of being so stoned during family concerts that he would become carried away by a single note on the bass guitar he was playing. He would play it over and over while the rest of the family attempted to continue singing, pretending nothing was happening.

By the time he was in his 20s, he’d had enough of the sham and completely turned his back on anything to do with God. Because of his musical ability, he quickly excelled in secular country and rock.

“When Elvis died, he choked to death on his own vomit,” LeFevre tells the kids. “Now that’s not pretty, but it’s true.”

He hesitates, surveying the crowd. The same teenagers on the front row who were wildly cheering his last song are intently taking in every word he has to say.

“Let me tell you,” LeFevre drawls in almost a whisper, his mouth close to the microphone. “Castles are lonely.”

“Jesus loves me, this I know,” LeFevre begins to sing, “for the Bible tells me so.”

At age 39, LeFevre has come full circle.

Once again he is part of Mt. Paran Church of God, the church his musical Southern gospel family called “home” back in the days when they lived “on the road” constantly on concert tour.

Once again he is singing “Jesus Loves Me.” But this time, he’s neither on narcotics nor mocking the trusting crowd. We have some good news to tell you here tonight,” he declares. “Jesus loves you. “

He holds up a Bible and soon is preaching out of Colossians, chapter one. An hour later, he is leading an emotional, 45-minute altar call. Kids stream to the front for prayer, counsel, deliverance, repentance and salvation.

Kneeling at the altar, LeFevre talks with a girl who is weeping and wanting to know what she’s supposed to do to tum her hurting heart over to Jesus.

That’s something LeFevre didn’t do himself until 1979, when he was 34.

For years, LeFevre sang about a Jesus he didn’t know.

He began his musical career in 1949 at age 4. His mother and father, Urias and Eva Mae LeFevre, put him before a stage microphone and let him join a concert of the Singing Lefevre Family. The cute toddler was an immediate hit and a natural ham, playing to the audience like a veteran performer.

But becoming a featured part of such a ministry didn’t automatically make little Mylon a Christian. He lacked any relationship whatsoever with Jesus.

Everything was show.

As he grew older, he learned he had to maintain a grandiose act of being a good little Christian if the family’s albums were going to sell and if the Singing LeFevre Family was going to remain in demand at concerts.

“My mother was always a godly woman, but my daddy was a real hard man,” he remembers. The family ministry was a business first, an artistic outlet second, then an outreach only incidentally.

Young Mylon remembers being “forced” to go to church. “I went, but I never listened,” he says. Traveling and performing, the boy began writing gospel songs, but was filled with conflicts and contradictions. He didn’t believe what he sang, and thus when he was rejected by other kids, was filled with anger.

Boys his age assumed the little “preacher-boy” didn’t want to hear dirty jokes. But he did—if it meant being included. They figured he wouldn’t want to be part of pranks or troublemaking. But he most desperately did.

Unlike a youngster who has a real relationship with the Lord, young Mylon was spiritually alone, trapped by a false “religious image” he had to maintain, believing none of the Christianity his family’s image required.

He was a successful religious songwriter and singer, but was also a deeply cynical and bitter young rebel. He became a troublemaker—also for effect. Unable to step off-stage even among his peers, he tried to make a name for himself with other kids and band members. He showed them he was worse than they—more daring, more exciting, more worldly. Alone he retreated into drugs, fighting against the legalism and falsity of his unchosen career.

From the first, he was completely open with his family about his drug use. As a pre-teen, when he smoked marijuana for the first time with older friends, he called up his parents and told them that getting high was great and that they should try it, too.

It appears that Eva Mae and Urias LeFevre didn’t know what to do about their tormented, gifted, rampaging little boy. He had gotten out of their control too quickly.

They tried to blink at his screams for help—looking the other way as long as he kept his ever-growing mutiny a private family matter. Trouble began only when he became more public and threatened to sully the singing family’s image as godly people.

Father and son began yelling and arguing and trading accusations publicly. Mylon was sent off to, then expelled from, several schools. Yet, despite his deepening rebellion and increasing drug use, his first gospel record was released when he was 12.

He was a very precocious 12 in other ways.

“I first met my wife, Ann, when I was 12 years old and singing at the Grand Old Opry with my family,” he recounts. “I saw her sitting in the audience and thought she was the most beautiful girl I’d ever seen.”

In storybook fashion, he asked her to share a strawberry soda after the concert. They corresponded for several years while he traveled on the road with his family, but eventually lost touch with each other.

Then when he was 17, his gospel song, “Without Him,” was recorded by Elvis Presley. LeFevre became wealthy virtually overnight. In the first year, he made $90,000 in royalties. His rebellion intensified.

Then “after Elvis recorded it, 126 albums were released with that song on them,” he remembers. Groups and artists such as the Imperials, Pat Boone and the Bill Gaither Trio began recording Mylon LeFevre compositions.

They had no idea there was nothing behind the religious façade of the talented boy from the respected Singing LeFevre Family.

Young LeFevre had learned how to fake Christianity in his songwriting just as easily as he could fake it in his public performances.

He knew what people wanted to hear and see and feel.

At age 22, he ran into his future wife, Ann, again.

“At first I didn’t recognize her,” he remembers. “She was all grown up, a woman. But I fell in love with her all over again and we got married in 1967.”

She had gone through a brief rebellion, but was ready to settle down. A devoted Christian, she began a long, difficult decade of praying for her wild husband.

His drugs continued—as did his participation in the family ministry.

But tension continued to build between him and his parents—particularly his father—over increasing disregard of the family’s carefully maintained public image.

Finally, in a heated argument over the length of his sideburns—not his drug use—he was kicked out of the Singing LeFevre Family in February 1970. After recording 33 albums with the LeFevres and the Stamps Quartet, the 24-year-old was on his own.

But he was rich from royalties on his songwriting.

He remembers laughing—he didn’t need anybody, particularly the family gospel music business.

He had everything he wanted.

He easily found other work and over the next 10 years performed on records, concert stages and TV with the likes of Little Richard, Billy Joel, Eric Clapton, Willie Nelson, The Who, The Rolling Stones, George Harrison and others.

But although he was addicted to heroin and constantly experimenting with a variety of other drugs, he remained drawn into Christian music.

“‘I was singing songs about Jesus with a rock ‘n’ roll band when they hadn’t even invented the term contemporary Christian music,” he remembers. “Back then, it was like a ’cause’ for me to do contemporary Christian music, like having the right to wear my hair a certain way.”

But the influence of the drugs was stronger than that of the religious music he sang. He fell into a cycle. He would spend every cent he had, then record a new album, go on a concert tour, make thousands of dollars, spend every cent on drugs, parties, other women, excitement and more drugs. Then, his money gone, he would record another album— sometimes religious, other times not—and go back on tour.

“She had every reason to divorce me,” LeFevre says of his wife. “But she stayed.”

And she prayed.

That may have been the only thing that saved Mylon LeFevre—the fervent, constant intercession of a woman who dearly loved him.

One day in 1974 he overdosed on heroin, but lived. His heart actually stopped, which scared him—and terrified Ann. He began attending services with her, but quickly was irritated by churchgoers’ negative reactions to him.

“I found a Bible study where they ignored me,” he says. “I would go even if I was stoned. I was trying to seek the Lord, but I wasn’t really sold out. “

After the Bible studies, Mylon would often meet friends to discuss the Bible and snort cocaine. This double life went on for years as the battle for his soul raged inside.

“I must have gone to the altar a hundred times over the years,” he says. “No one ever got across to me that when you’re free in Jesus, you’re free indeed. “

Then in August 1979, his father lay dying of cancer in an Atlanta hospital. “One day, I went to the hospital to see my daddy and he started telling me about Jesus,” LeFevre remembers. “Now, I loved my daddy, but I never liked him. We never got along. We hadn’t spoken to each other in a long time. I was going to the hospital because he was dying and I felt guilty.

“But that last year before he died, he started reading the Word of God, and God really broke his heart. The Lordship of Jesus Christ became real in his life. When I saw this hard, cold man that I never wanted to be around become a sincere, kind, gentle person, then I began to visit him because I wanted to, not out of guilt.

“I told him I loved him and if I’d known our relationship could have been like this, I wouldn’t have spent all these years fussing and fighting with him. “

Mylon was unprepared for his father’s reaction. Urias LeFevre was a big man, 6-foot-five and 280 pounds. Mylon had never seen him cry. But he cried that night. He told Mylon, “Son, Jesus has really come into my life and really touched my heart. ‘

Deep in Mylon’s heart, a years-old longing was met, a chord was struck and the son answered the father with tears of his own.

Mylon went home that night and asked the Lord to do a miracle in his life like the one He had done in his father’s.

“Nobody knew when I became a Christian because I didn’t tell anybody at first,” he says. At a loss as to where to seek fellowship, he remembered his family’s old home church, Mt. Paran Church of God in Atlanta.

He slipped quietly into a service. But he was recognized by old-timers and staff.

He was welcomed home like a prodigal son.

“I just started going to church at Mt. Paran and the people there just started loving me,” he says simply.

Youth minister Mike Atkins remembers, “He was so burnt out, you couldn’t hold a conversation with him. I’d spend time sharing Scripture with him and at the end he’d say, ‘Huh?’ The drugs had just burnt him out.

“The most astounding thing about Mylon was the effect the Word of God had on him,” Atkins remembers. “For a long time, he came to Bible studies and then the Word began to take root in his heart. As it did, it began to heal his mind. By the time he finally stood up to sing to the kids at church, he was truly anointed by God.”

But still LeFevre dabbled in the drugs that had been a vital part of his life ever since before the teenage years.

The last time LeFevre took drugs was in 1980, he says. He tried to witness to a rock star friend, who instead got him to get high for “old times.”

“I tried to tell him about the Lord, but I was in the flesh,” says LeFevre. “I was so guilty and frustrated afterwards and the Lord told me, ‘Look, you don’t have to go through this again.’ What He showed me was I simply needed to draw close to Him.

“I don’t go to rock concerts anymore,” he adds.

The healing of LeFevre’s mind after more than two decades of drug abuse amazed Atkins. But another—healing is more amazing to LeFevre: the healing of his marriage.

“Jesus forgave me and that’s miraculous,” he says. “But sometimes I feel Ann’s forgiving me and loving me is even more miraculous. What God has done in my marriage, I can’t tell you in words.”

As LeFevre’s faith increased and as his personal discipline developed, Mt. Paran’s confidence in him grew. The music that had so long been a part of life finally meant something to him.

He now sang about a Lord with whom he had a deep and personal relationship.

He began a youth outreach with a band of Christian friends formerly in secular rock. They called themselves Broken Heart.

At first, they only played at Mt. Paran.

Then they began to get invitations to perform elsewhere. Some were accepted, some weren’t. It wasn’t felt at first that LeFevre was ready to minister to others without supervision from the Mt. Paran staff. He was still recovering, healing and maturing in the Lord.

LeFevre was put on the youth ministry staff. Then a separate department was formed, the youth outreach department. He became the youth outreach pastor.

He began traveling nationwide.

This time when he sang for Jesus, his words had deep meaning. This time, when he preached and prayed, it was real and intense.

Unlike in the concerts of his youth, LeFevre doesn’t perform light, Christian entertainment. He uses imaginative, mainstream rock ‘n’ roll to draw kids. He plays, sings, witnesses and preaches with intensity.

LeFevre says he is determined not to let his growing national popularity turn into the money-centered type of Christian business he grew up in. “We don’t advertise and we never have had an agency to book concerts,” he says; “We just answer the phone at church and if people invite us to come and minister, we pray about it. We never say, ‘OK, we’ll come if you give us X amount of dollars.’

“My purpose for going out on the road is not T-shirt and record sales. I was already selling millions of records. My purpose is those people in our prayer room after a concert—the ones who come down at the altar call. My life no longer belongs to me. The One who’s running my life is doing an incredible job. I couldn’t buy that with $20 million.”

Michael Coffey, a Christian concert promoter in Richmond, Virginia, says of LeFevre:

“There are three ways to look at things when it comes to Christian concerts—as ministry, as business or a balance between the two. Mylon is one of the unique people on the road today in that he has proper balance. His main priority is the ministry of the gospel. He has developed his faith to where his hard-hitting sermons are intertwined into the lyrics.”

“We’re in a spiritual war, you know,” LeFevre says. “We’re competing against (non-Christian) groups like AC/DC, Judas Priest and Van Halen for minds and souls of young people. We’re seeing thousands come to Christ.”

Because LeFevre believes in using the medium of rock ‘n’ roll to change lives, LeFevre and Broken Heart have signed a new contract with CBS records. The group refused to sign the contract until a CBS executive came to one of their concerts—altar call and all—and agreed to the band’s stipulation for total Christian, evangelistic content on the secular label.

The group also has a music video which is being played on MTV, the cable television rock music network. “Our ‘Stranger to Danger’ video is being seen in 30 million homes,” says LeFevre. “That’s about 70 million people watching us sing that Jesus is King of kings and Lord of lords.”

As Mt. Paran’s outreach minister, LeFevre has an office at the church, storage space for his band’s 22 tons of concert equipment, a new, custom-built, 40-foot bus and a church-supplemented budget. As the youth outreach pastor, he remains under the church leadership’s authority, where he says he intends to remain.

Although the Lord has restored his mind, talent and vitality—making the onetime, vacant-eyed addict into an articulate, fiery preacher—LeFevre values the church ‘s spiritual covering over him, the guidance of senior pastor Paul Walker and church members’ intercession for him and the band while they’re off in concert. {eoa}

Join Charisma Magazine Online to follow everything the Holy Spirit is doing around the world!

Audrey Hingle wrote for a number of Christian and secular magazines, including Christian Herald and Saturday Evening Post.