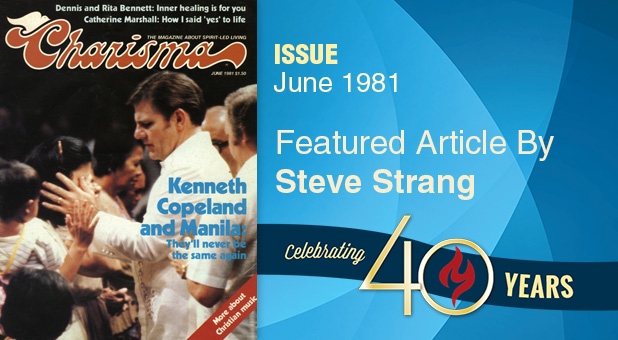

Kenneth Copeland: ‘They’ll Never Be the Same’

Copeland asked those who had been healed to come forward.

No one responded.

Copeland then asked the people to begin praising God.

He finally asked the tour members to spread out in the crowd and pray for people.

The tour members were eager. They spread among the Filipinos and began praying in groups of two or three. A few began casting out demons and shouting at illnesses.

One 6-foot, 200-pound American preacher pounded with one hand on the back of a 5-foot Filipino man, while waving the other hand wildly over his head.

Minutes passed as these mini-healing services took place throughout the coliseum. Copeland seemed awkward. Finally, he said “no one get nervous. We’re just going to follow God.”

Just then, someone rolled an emaciated-looking 30-year-old Filipino man to the edge of the platform. Copeland leaned over the edge of the platform, laid his hand on the head of the man and shouted, “In Jesus’ name, be healed!”

The man slowly pushed himself to the edge of the high-back wooden wheelchair, braced himself with both arms and laboriously raised himself. He took four or five halting steps forward and caught himself on the edge of the platform.

The crowd went wild. People began praising the Lord, yelling and clapping.

But it was obvious the man was experiencing excruciating pain. Before the man collapsed, Copeland rebuked pain, and let him return to his wheelchair.

When Copeland asked Gloria and Sumrall to form three healing lines in front of the platform it looked as if half the crowd came forward for healing.

After everyone was prayed for, Copeland led those who wanted to be saved in a sinner’s prayer, prayed for marriages to be restored, and prayed for the unemployed to find jobs. Everyone applauded. (Unemployment is a problem in the Philippines where the average daily wage is the equivalent to $4 a day.)

Then, to the strains of “How Great Thou Art,” the meeting abruptly ended. Copeland hurried to a waiting car.

Meanwhile, I had worked my way through the crowd to the man in the wheelchair. His name was Romeo R. Pakingan and he had been operated on three times for malignant tumors. He told me through an interpreter the doctors hadn’t given him long to live, but he believed he had been healed.

Later in the week I saw him in the meetings again still in his wheelchair. There was no obvious indication of healing.

I had watched the faces of the people as Copeland prayed for Mr. Pakingan, extending their hands toward him to show their faith. They strained to join their faith with Copeland’s, wanting so much to see a miracle happen, wanting so much to see the man be healed.

If the people were disappointed, they weren’t half as much as Copeland.

Copeland told me en route back to America that he was discouraged after that first meeting. He had been advised by many not to offend cultural sensitivities and felt he could not be himself.

He said his ministry differs from other American evangelists who rented the Araneta. Yet a platform, complete with center ramp, had been built so the miracle cases could be paraded before the admiring crowd as some evangelists like to do.

That isn’t his style. So Copeland sequestered himself in his hotel room and sought God on what to do. The next night the long ramp was gone.

“I really admire him for sticking with it after such a dismal start,” said David Sumrall, pastor of Bethel Temple who drove Copeland back to the hotel after that first service.

“He didn’t say anything negative about how he felt,” Sumrall said. “But I saw his face. I could see how low he was. A lesser man would have given up and gone home right then. He saw he had to change. He did the things he felt he had to do. It took a big man to do that.”

If there weren’t enough problems already, David Sumrall began getting negative comments about the tour members’ behavior in the meeting. Apparently they were not sensitive to the Filipino culture.

Some Filipinos resented that the foreigners were ushered to positions of honor front and center in the coliseum, while the Filipinos had to sit in the grandstands behind them. Others said the tour members were too rough when they prayed for people the night before. A few had pushed over the smaller Filipinos in their zeal to lay hands on them or to see them “go down under the power.”

David Sumrall asked to talk to the tour members the next day. “These are a gentle people who love to love and love to be loved,” he said. “Speak gently to them and with the love of God. Reach out. People respond to love. It is still the same in any language. Just smiling under the anointing will cause burdens to break. Mingle with the people. Get in the middle of them.”

His talk seemed to work. The tour members quit sitting together. They became more aware they were guests in another country. They developed a rapport with the Filipinos. By the final night, hundreds of Filipinos crowded the bus stop outside the coliseum to wave goodbye to their new friends as they were taken back to the hotel.

Filipinos are generally pro-American. President Marcos is one of the United States’ greatest allies in the Orient.

They wear American-style casual clothes. They listen to American music and watch American television reruns. When I was there, the big rage was disco dancing—something John Travolta made popular over here a few years ago.

English is a major second language taught to all Filipino students in secondary school. Almost all commerce, and all street signs or products in stores are in English.

However, this proud nation has nine major languages and 90 dialects although the government is trying to make Tagalog the national language. The sensitive evangelist understands and does not try to force American culture, customs or language on the people.

But Copeland’s meetings were held entirely in English, except for songs he sang in Tagalog. I couldn’t understand why the meetings were not translated—especially when Lester Sumrall told me this was the first evangelistic crusade conducted in Manila without an interpreter. Maybe it was because each meeting was televised for possible rebroadcast in the United States.

Even though most of the people who came to the meetings could understand English, Sumrall told me at least 10 percent of the people could understand nothing that was said. Another large percentage couldn’t speak English well enough to understand much of what was said.

When I tried to interview Filipinos, I had difficulty communicating unless I was with an interpreter who spoke Tagalog.

(Interestingly, en route back to the United States, Copeland told me of an unconfirmed report he received from Billy Rash, his associate. Rash said a woman told him that her elderly mother who spoke no English understood none of the service until Copeland began to preach, then she understood everything perfectly. “That’s just like the Day of Pentecost,” Copeland said.

Copeland told me that story sitting in Narita Airport outside Tokyo waiting for a connecting flight. Dressed casually in white slacks and a blue knit shirt, Copeland admitted he felt weary after the eight-day crusade—like air let out of a balloon.

Seated in a Japan Airlines waiting area, Copeland and Gloria shared their feelings about the crusade.

“I found out I had to believe God for things I didn’t know I’d have to believe God for,” Copeland said, lightly tapping the plastic arm of his chair for emphasis.