Anyone who hears Allen Hood speak will be moved by the passion for Jesus he expresses. I first heard him preach during my college years when I attended a conference, and since then I’ve consistently sought out his latest messages—partly because he addresses issues of injustice as few Bible teachers do.

Since 2000, Hood has served on the leadership team of the International House of Prayer in Kansas City, Missouri. A husband to his wife Rachel, father to three sons and associate director of IHOP-KC, he teaches often on the splendor of Jesus Christ and His global plan for humanity. Along with being committed to worship and prayer arising in the earth, he has a heart to see unity in the body of Christ as well as racial reconciliation.

In a phone interview, Hood shared life experiences that opened his eyes to racism and deepened his love for the black community. Bound4LIFE has always been a movement of prayer and advocacy to halt innocent bloodshed—whether that has occurred through abortion, systemic bias or other ways our society devalues lives.

Our discussion went many places, but I believe a few of Allen’s personal stories give a strong foundation for moving the conversation forward.

“Most of my childhood was in north Florida,” began Hood, revealing how he saw racism and bigotry flaunted in the words and actions of his own grandparents.

“I heard all sorts of cultural lies about black people, who were referred to in very derogatory ways: that they’re lazy, they don’t want to work, they want a free handout—every kind of lie that you can imagine with regards to their housing, transportation, work ethic and their raising of children,” he said.

Even though Hood’s grandparents went to church, the racism they had was still deep-seated in their hearts. “Praise God, my mother and father were not racists, and they trained us differently,” he continued.

He was in middle school during the 1970’s, at a time and place when desegregation was still working itself out. “The Civil Rights Movement had ended and desegregation was on the books, but it was not being applied in most counties in Florida,” he said. “As a poor white boy, I was bused to a predominantly black middle school.” This was the start of his journey in race relations.

He continued, “Most of my friends were black. I was the only white guy on the basketball team. I got to throw the ball in as the ‘token’ white guy. I got to feel the different experience. But I had close black friends.”

Gradually, Allen began to question his accepted notions about race and privilege. He recalls hanging out with a teammate one day. “I would go to his house and I’d notice: the window screens were out, the roof leaked—and yet they had a brand-new Cadillac in the backyard.”

Allen thought of what his grandfather used to say—that black people would buy brand-new cars but wouldn’t even take care of their houses—but it didn’t add up.

With boldness, he asked his friend’s mom: “Mrs. Lewis, you have a brand-new Cadillac out there. My family can’t even afford a Cadillac, and my dad has a good job. Yet your house has leaks in it. I’m not trying to offend you, but can you tell me why?”

“And I will never forget it. She said, ‘Let me tell you something. I’d like to have a home like your home, but the bank won’t give me a loan. The white landlord who owns my house won’t let me buy this house, and he won’t lift a finger to fix anything on this house. So guess what? That car outside is the only thing I own. It is going to be the best car and the best-kept car on the block.'”

Suddenly, Hood realized how the suffering of his black brothers and sisters was being further extended by lies that had taken root among the white majority in America. “That conversation changed me; I would never be the same,” he told me.

Years later, in 1987, another experience opened his eyes to the devastating impact of systemic racism—when he was coaching a basketball team comprised only of black players. The starting five visited Allen’s home to eat before the game.

“Our center asked me if he could use the bathroom,” recounts Allen. “He said, ‘Allen, I’ve got to go. I promise you I won’t touch the seat and I will strike a match.’ I told the young man I was confused—thinking, Of course he can use the bathroom. But he told me the same thing [again].”

“Trying to get clarity with him, I asked, ‘Do you have to go No. 1 or No. 2?’ Vick said, ‘I’ve got to go number two, Allen, but I will not sit on your toilet and I will strike a match.’ I replied, ‘Vick, strike a match, but bro: sit on the toilet.’ And you know what he said? He replied, ‘No, I won’t—I’ve never been in a white person’s house, and I was told I better never use their toilet.'”

This young man’s fear of using the Hood family bathroom—because they were white—moved Hood. He told me, “That cut me so deeply. I thought, What is in the psyche of an 18-year-old young black male in Florida? It broke me.”

Hood set his heart to learn what has ailed and impacted the black community. He decided to fight to come out of the cultural strongholds that were handed down to him by his grandparents. He needed to understand, and the first step would be to listen.

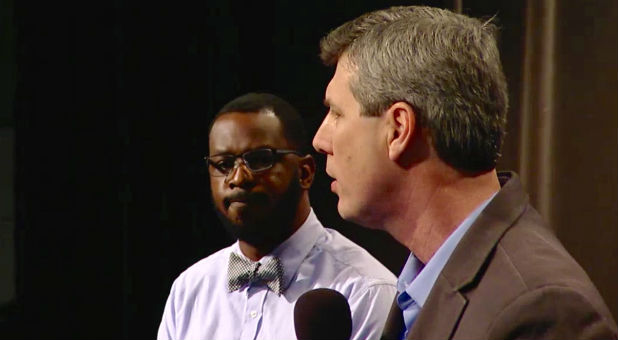

Today, he continues to listen—but he speaks as well from what he’s learned. In a panel discussion at IHOP-KC on “Understanding the Racial Climate in America,” black Christian leaders and Hood addressed current events from a biblical perspective. It’s well worth watching as Americans grapple with how issues of race and justice can progress in the new year. {eoa}

Christina Marie Bennett, who writes at ChrisMarie.com and Bound4LIFE, believes conversations can change culture. After graduating college with a degree in Business Communications, she served with Bound4LIFE International—a faith-based pro-life group based in Washington, D.C. Since then, she married the love of her life and became a stepmother. She currently works for a nonprofit in New England that serves pregnant women in crisis and their families.

Reprinted with permission from Bound4LIFE.