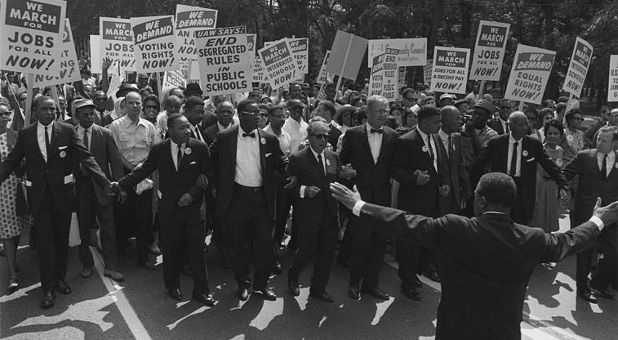

Memories of the March: 10 Voices Recall 1963 March on Washington

Religion News Service asked participants in the 1963 March on Washington to reflect on their lasting memories of the event and how it shaped their faith. Their comments have been edited for length and clarity.

Don Cash had graduated from high school in June 1963 and decided on the spur of the moment to join the March on Washington when he finished his work shift at a nearby warehouse. The Baptist layman is the president of the United Food and Commercial Workers Union’s Minority Coalition and a board member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the NAACP.

“I think we got a long ways to go but I do think that there’s been a lot of changes,” he says. “I don’t think you’ll ever see what Martin Luther King dreamed in reality, in total. I think we’ll always have to strive for perfection. The dream that he had is a perfect world and I think that in order to be perfect, you have to continue to work at it.”

Dorothy Cotton was the education director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was co-founded by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., in the 1960s. She and other civil rights activists were staying at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., when King was assassinated.

“African-American people en masse and all of our wonderful white allies who worked and suffered with us, we had confidence ’cause we felt it, ’cause we had been working to change this evil system for years,” notes Cotton. “African-American folk had changed how we saw ourselves. We were no longer going to let an evil system define who we were.”

The Rev. Eugene Pickett, former president of the Unitarian Universalist Association, was pastor of the Unitarian Universalist Congregation in Atlanta in the 1960s. He met the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at a luncheon arranged by a dentist who was a member of his congregation. King’s children integrated the elementary school attended by his three daughters.

“I had served churches in the South since 1952,” he recalls. “Improving race relations and working for racial justice had been a high priority for my ministry. So the march was a moving and affirming experience as well as an energizing one. I went back to my congregation with a deeper commitment to work to further Dr. King’s dream. When I became president of our Unitarian Universalist Association I continued to make racial justice a high priority for our movement.”

Rabbi Richard G. Hirsch, former executive director of the World Union for Progressive Judaism, was the founding director of the Reform movement’s Religious Action Center in Washington from 1962 to 1973. He met the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1962, and organized the Jewish participation in the march.

“We have come a long way, but as society advances in the direction of what yet needs to be done, we recognize that our perception of the ‘perfect society’ also advances. The more we advance the more we see that more has to be done,” explains Hirsch. “Our perception of what was called the ‘Great Society’ is like the horizon. The more we proceed, the more we recognize how far we have to go. The march was very important and very successful … but in the final analysis it was only an important link in a long arduous chain of events and daily sacrifices of millions of Americans in a drama which is still unfolding.”

Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga., is the last living speaker at the 1963 March on Washington. An ordained Baptist minister, he was chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in the 1960s, which was known for its sit-ins and other civil rights movement activities.

“My faith has been strengthened to be not afraid but to be courageous and find a way to get in the way because of the March on Washington,” he says. “I saw on that day hundreds of thousands of people representing different religious communities. I saw people carrying signs. I saw people marching with their feet, saw people speaking up and speaking out with their feet through their faith. My faith has been strengthened, and if it hadn’t been for the March on Washington, I don’t know what would have happened to me.”

The Rev. James McLinden, pastor of St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church in Baltimore, made a pledge with another novice to participate in the march after completing their training in New York state with the Josephites, an order of Catholic priests and brothers committed to serving the African-American community.

“I think the lasting thing was just the exuberance of the crowd itself. We had the sense and the spirit and the speakers, and just the crowd—I mean it covered that whole area. It was a very wonderful experience, and I’m very glad we made that intention in the novitiate to do that,” comments McLinden.

The Rev. Gilbert H. Caldwell, a retired United Methodist minister, took part in numerous civil rights activities and introduced the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at a rally on the Boston Common. He was an assistant pastor of Union Methodist Church, and director of Cooper Community Center, both in Boston, at the time of the march.

“The interracial rainbow of people in attendance at the march brought tears to my eyes,” he recalls. “I was a 29-year-old assistant pastor when I went to the march. I had been discouraged by the fact that many white persons in the church had not yet embraced the meaning of the civil rights movement for their own faith journeys. Some Methodists in Boston, pastors and lay people, were bothered by the name of the march. They felt that the use of the word ‘on’ Washington was too provocative and militant. And, they had been brainwashed into believing that the march would end up in violence. The presence of white persons at the march was a source of encouragement to me that is difficult to explain.”

The Rev. Robert Graetz is a white Lutheran minister who pastored a predominantly black congregation in Montgomery, Ala., in the 1950s. Civil rights activist Rosa Parks was his neighbor. He was living in Ohio when the March on Washington occurred.

“Even though we had had many other people from different faiths and different ethnic groups taking part in particular parts of the civil rights movement, it was clear that that massive turnout of people—ethnicities, all economic levels, everything imaginable—(showed) there’s something to the promise of the beloved community that Dr. King used to talk about. It gave all of us a real boost in terms of what the possibilities might be,” explains Graetz.

Glen Stassen was a graduate student and co-organizer of a Christian interracial association at Duke University that worked with other civil rights groups in Durham, N.C. He organized two buses that traveled to the march. An American Baptist layman, Stassen is now a Christian ethics professor at Fuller Theological Seminary.

“There was a lot of anxiety about whether the march would come off nonviolently. This was not so much anxiety by those of us who were organizing for it, but it was by the persons not into the African-American struggle for justice,” he says. “The second kind was: Will the people show up or will it be a flop? As we were arriving in Washington in our bus, (we saw the streets) just loaded with buses. It was such a celebration. It was gonna happen. People would be there. That was such a lift.”

Myrlie Evers was newly widowed at the time of the march. Her husband, civil rights leader Medgar Evers, was killed in June 1963. She was scheduled to be a march speaker but only reached the edge of the crowd. She gave the invocation at President Obama’s second inauguration.

“Perhaps missing the opportunity to speak at the march in Washington 1963—and the first program is printed with my name on it—was the best thing because I was hurt; I was very, very angry,” she explains. “I was dealing with a split personality—one that said, ‘Move forward; don’t hold the anger within you,’ and the other part of me said, ‘Vengeance will be mine.’”

Copyright 2013 Religion News Service. All rights reserved. No part of this transmission may be distributed or reproduced without written permission.