‘Demons From Hell Were Unleashed Like Seething Lava Over Our Land’

I have heard that in the United States, people remember exactly what they were doing when planes hit the Twin Towers in New York. In Rwanda, too, we remember a plane crash that way. On the evening of April 6, 1994, an airplane carrying President Juvenal Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira, both Hutus, was shot down as it arrived in Kigali, the Rwandan capital.

There is this difference: On Sept. 11, nearly 3,000 people died. In Rwanda, smaller in size and population than Ohio, the deaths of the two presidents set off a genocidal rampage against the Tutsi people that killed three times as many as died in 9/11—every day for 100 days.

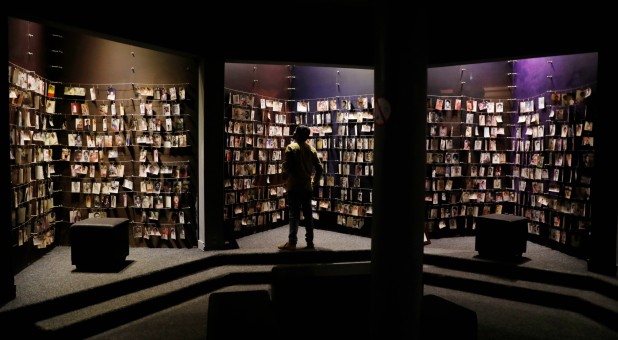

I’m trying to help people grasp what happened, because no one can picture a million human beings killed. Not even we who survived.

April 7, the chosen launch date for the systematic slaughter of the Tutsi population, was Day One of our country’s Hundred Days in Hell.

The killing reached my town, Bugarama, in western Rwanda, on April 16. How gladly I would forget all I saw that day, but—as war veterans can confirm—such images are seared into the brain as if by a camera’s flash.

Why revisit that day’s events, then, if they were so horrific? I feel I owe it to the people who died; if I don’t tell, who will even know that they lived?

Also, I write for the sake of history. If a nation’s shameful deeds are not to be repeated, they must be recognized and remembered—not swept under the rug. As harsh as it is, American youth need to learn how Native American peoples were exterminated; Germans have to know what their country did to the Jews; and Turks must acknowledge the Armenian genocide. Mass evil can break out at any place where one group despises another.

In Bosnia, people who had previously lived peaceably as neighbors carried out the 1995 massacre of Muslims at Srebrenica. And in 2017, ethnic cleansing in Myanmar claimed around ten thousand Rohingya lives.

So, as a witness to the genocide against the Tutsi, I must tell what happened, no matter how painful it is for me to write. I hope my account will help ensure that nothing like this ever happens again, anywhere on earth. But I also write because genocide is not the end of the story —not for me and not for my beloved country.

It is still hard for me to believe that the sun rose as usual on April 16, but in fact, it was a beautiful Saturday morning. I could hear birds singing. The sky had cleared again, with no sign of rain. If it hadn’t been for the dread weighing me down, this would have been the perfect day for scrubbing my floors and for washing and hanging out the laundry. I had always been an energetic mother and liked a clean house, especially with a baby on the way.

But with all the recent happenings, I woke feeling overwhelmed, my mind tuned to an inner vibration—or was it a distant drumbeat? In this state, I could face only the most basic tasks. I tried to fix my mind on feeding 18-month-old Christian,4-year-old Charles-Vital and the others in my apartment, and then on cleaning up after breakfast. I felt strung tight—listening, watching— and kept glancing out the window.

It was a relief, around 8 o’clock, to see my friend Faina approaching, an empty basket on her head. She was a Hutu woman I had often prayed with. Her family was poorer than ours, yet she had a generous nature, and she came now to ask if I needed anything from the market in Nyakabuye.

Touched by Faina’s offer, I gave her enough money to buy cabbage, plums, bananas and lenga lenga, a spinach-like vegetable. My heart lifted a little at her thoughtfulness—and at knowing that my household would have fresh food through the weekend.

At noon, it was time to prepare lunch, but, surprisingly, Faina had not yet returned with the fruit and vegetables. Twice, I glanced up the road to see if she was coming. The third time I stepped out, I saw a figure in the distance, running our direction. It looked like Faina, but I had never known her to run, and this woman was empty-handed.

As she came closer, I saw that it was indeed Faina—but she was almost unrecognizable. I hurried to meet her at the gate.

She was so upset and breathless, I could hardly make out her words: “Denise … your Aunt Priscilla … her two children … her father-in-law … terrible … in a ditch … Priscilla still alive. …

“Asked for water … said to warn… killers coming… destroy all Tutsi!” Turning, Faina fled toward her own home.

I froze at her news. But I had to raise the alarm. Dashing through my house and out the back door, I cried, “We are all about to die!”

“I sense that some of us will die today,” I said, to a background of far-off shots and yells. “For those who are killed, Rendez-vous au ciel — we will meet in heaven.”

Kneeling in the hallway, we prayed aloud, asking God and each other for forgiveness.

How could ordinary people veer from a normal life — looking for work, studying at college or earning a living — to butchering others?

I can only answer that demons from hell were unleashed like seething lava over our land. Not the comic-scary hobgoblins of my mother’s legends, but cosmic forces before which human beings are dust specks in a volcanic explosion.

That is not to say that individuals don’t count. I believe that each one murdered was welcomed into the next world, just as I believe that each who survived was saved for a reason.

We who lived faced a harsher task; I often felt death would have been preferable. How hard it has been, through grueling years: to overcome the loss, battle to forgive and then bring healing to others — yes, even to killers. They, too, were specks of dust.

In the West, many people scoff at the idea of invisible spiritual powers. I’m sure some of these skeptics would acknowledge the reality of such powers, however, if they had been caught in a firestorm like ours.

United Nations General Romeo Dallaire wrote, “In Rwanda I shook hands with the devil. I have seen him, I have smelled him, and I have touched him. I know the devil exists, and therefore I know there is a God.”

I believe each of us plays a role in this spiritual war, and each soul decides to serve life or death. There is no neutral. Death had a grip on Rwanda in 1994, but it has a grip in other places, too, and has other weapons besides machetes and grenades.

Also, although a plummeting plane ignited our inferno, the tinder had been accumulating a long time: division, envy, hatred and the labeling of Tutsi as vermin. For the rest of my life, I will protest the least insinuation that any person or group of people is less than human.

© 2019 Religion News Service. All rights reserved.

(Adapted from From Red Earth: A Rwandan Story of Healing and Forgiveness © 2019 by Denise Uwimana, published on April 6 by Plough Publishing. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.)

Listen to the podcasts for on-the-ground coverage in Rwanda with perpetrators and survivors of the genocide.