JFK and the America We Have Lost

This week, those of us who are old enough to remember that dreadful Nov. 22 in Dallas a half-century ago find ourselves awash in nostalgia for a more innocent time in our own and the nation’s life.

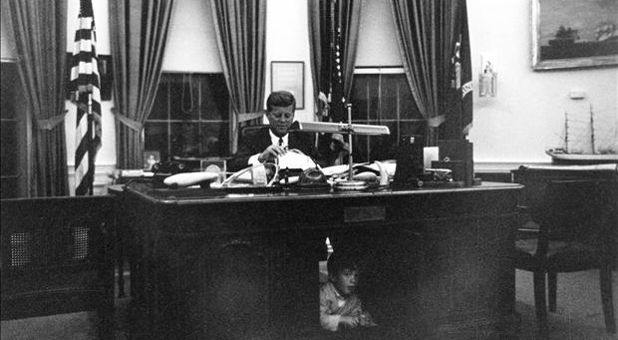

We get that catch in the throat at the poignant images of Camelot served up in a dozen television specials. We join in the wild speculation of the greatest “whodunit” in history and ask ourselves for the umpteenth time all the “what ifs.” What if Oswald had missed his mark? What if the bubble top had been on the limo? What if JFK had lived? How differently would the tumultuous 1960s have turned out?

But looking back on that fast-receding time of our history, we are also reminded of the many ways things were different then, including the way we Americans high and low thought of and talked about ourselves as a nation.

This was brought home to me this week while speaking with a long-time American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ) client who has been on the receiving end of American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) lawsuits simply for wanting to express in public the same sentiments—indeed practically the same words—that John F. Kennedy so memorably proclaimed in his inaugural address when he committed his new frontier to “that same revolutionary belief for which our forbears fought: the belief that the rights of man come not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God.”

On that frigid January day in 1961, Kennedy did not hesitate to invoke a view of America that, in the intervening years, would come to be belittled—or worse, censored—from public discourse by a hypersensitive political correctness and the bullying litigation tactics of the ACLU.

No public official would say such things in 2013 without a twinge of self-consciousness that would have been foreign in 1963, without a nervous glance over the shoulder for the ACLU’s process server, without first running it by a team of constitutional lawyers.

But it wasn’t so in the Kennedy era. Consider that the rhetoric of the whole civil rights movement was imbued with biblical allusions and quotations. Indeed, Martin Luther King Jr. went directly from the Lincoln Memorial to meet with JFK in the White House following the “I Have a Dream Speech,” a speech in which King quoted the Psalms, Isaiah and the prophet Amos.

To Americans of that time—believers and nonbelievers alike—references to the Bible in political discourse were second nature, commonplace, even expected. Few would have guessed that in the ensuing years, they would become so controversial, let alone the stuff of seemingly endless lawsuits.

It’s not surprising, then, to read the closing lines of the speech JFK was prevented from reading at the Dallas Trade Mart on that Friday in November 1963, when he was cut down by an assassin’s bullets. The poignancy of those lines—with unmistakable allusions to Isaiah 62, Psalm 127 and Luke 2—is sharp enough, given the circumstances of their nondelivery. But 50 years on, that poignancy is magnified by the realization that, like the slain president himself, they belong to an America that is no more.

As Kenned said, “We in this country, in this generation, are—by destiny rather than choice—the watchmen on the walls of world freedom. We ask … that we may achieve in our time and for all time the ancient vision of ‘peace on earth, good will toward men.’ That must always be our goal, and the righteousness of our cause must always underlie our strength. For as was written long ago: ‘except the Lord keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain.”

Francis J. Manion is senior counsel with the ACLJ who emphasizes First Amendment law and pro-life legal matters before state and federal courts.