This Christian Awakening Ended Slavery in America

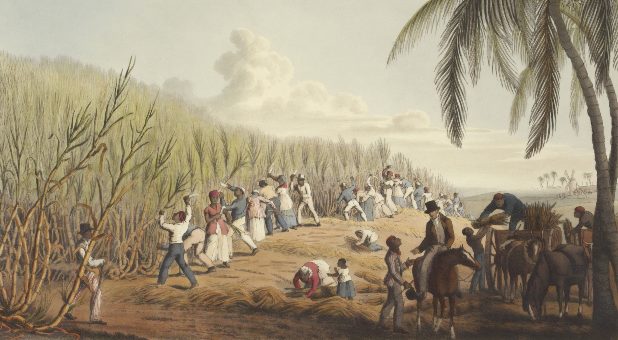

Historians have noted that slavery, though practiced for thousands of years by many peoples and civilizations, suddenly became anathema in 18th century America. The late historians Elizabeth Fox-Genovese and Eugene Genovese observed, “Perception of slavery as morally unacceptable—as sinful—did not become widespread until the second half of the eighteenth century.”

Dr. Walter Williams, professor of economics at George Mason University, has said that the unique characteristic of slavery in America was not only the brevity of its existence, but also the “moral outrage” against it. The brilliant scholar Dr. Thomas Sowell, who happens to be black, has written:

Slavery was just not an issue, not even among intellectuals, much less among political leaders, until the 18th century–and then it was an issue only in Western civilization. Among those who turned against slavery in the 18th century were George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry and other American leaders. You could research all of 18th century Africa or Asia or the Middle East without finding any comparable rejection of slavery there (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 90).

The Source of the Moral Outrage Against Slavery

There was a reason for this sudden moral opposition to slavery and that reason is to be found in what became known as The Great Awakening. In this Christian revival that ebbed and flowed from 1726 to 1770, it seemed that entire towns repented and turned to God. In his Autobiography, Benjamin Franklin described the amazing transformation of his hometown of Philadelphia in 1739. He wrote:

It was wonderful to see the change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seemed as if all the world were growing religious so that one could not walk through the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 79).

Out of this revival there emerged a deep concern for those who did not know Christ. As a result, many evangelists began taking the message of salvation to the marginalized of society, including blacks, both slave and free. Their ministries breached racial and cultural barriers and they saw many come to Christ. Black preachers and churches emerged out of this Awakening, as well as the moral outrage against slavery, which the historians above have noted.

From Evangelism to Social Transformation

At the beginning of the Great Awakening in 1726, outreach to the black populace was evangelistic in nature and not characterized by opposition to slavery. Those early preachers, such as George Whitefield, Gilbert Tennent and Jonathan Edwards, saw their primary purpose as getting people ready for the next world, not necessarily improving their lot in this one. In their thinking, a slave on his way to heaven was far better off than a king on his way to hell.

Nonetheless, their insistence on sharing the gospel with all people and their willingness to share Christian fellowship with blacks, both slave and free, breached racial and cultural barriers in Colonial America. Also, the inclusive gospel message they preached, and their compassionate treatment of blacks, created a climate conducive to the anti-slavery sentiments that would burst forth through those who would come after them.

Indeed, the revivalists who came after Edwards and Whitefield carried the message of their predecessors to its logical conclusion: if we are all creatures of the same Creator and if Christ died that all might be saved, then how can slavery ever be justified?

They, therefore, began a vicious attack on the institution of slavery. This is what historian Benjamin Hart was referring to when he wrote, “Among the most ardent opponents of slavery were ministers, particularly the Puritan and revivalist preachers” (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 92).

These “ardent opponents of slavery” included the followers of Edwards, who expanded on his idea of the essential dignity of all created beings and applied it to the blacks of Colonial America. They included Levi Hart in Connecticut; Edwards’ son, Jonathan Jr., also in Connecticut; Jacob Green in New Jersey and Samuel Hopkins in Rhode Island.

Showing the Hypocrisy of Demanding Liberty and Tolerating Slavery

Hopkins (1721–1803), who had been personally tutored by Edwards, pastored for a time in Newport, Rhode Island, an important hub in the transatlantic slave trade. Like Paul, whose spirit was “provoked” observing the idols in Athens, Hopkins was outraged by what he observed in Newport. He, therefore, began to passionately speak out against this “violation of God’s will” and declared, “This whole country have their hands full of blood this day” (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 92).

After the First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia in 1774, Hopkins sent a pamphlet to every member of the Congress, asking how they could complain about “enslavement” to Great Britain and overlook the “enslavement” of so many blacks in the colonies.

Indeed, as “liberty” became a watchword throughout the colonies, these second-generation Awakening preachers began applying it to the enslaved blacks in America. Like Hopkins, they pointed out the hypocrisy of demanding freedom from Great Britain while enslaving black Africans. One of the most vocal was the Baptist preacher John Allen, who thundered:

Blush ye pretended votaries of freedom! ye trifling Patriots! who are making a vain parade of being advocates for the liberties of mankind, who are thus making a mockery of your profession by trampling on the sacred natural rights and privileges of Africans (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 156).

The opposition to slavery thus mounted as other ministers of the Awakening began to speak out. For example, in a sermon preached and published in 1770, Samuel Cooke declared that by tolerating the evil of slavery, “We, the patrons of liberty, have dishonored the Christian name, and degraded human nature nearly to a level with the beasts that perish” (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 93).

God Speaks to Freeborn Garrettson

Freeborn Garrettson (1752-1827), a revivalist from Maryland, freed his slaves after hearing God speak to him supernaturally. According to Garrettson, he heard the Lord say, “It is not right for you to keep your fellow creatures in bondage; you must let the oppressed go free.” Garrettson immediately informed his slaves that they did not belong to him and that he did not desire their services without giving them proper compensation.

Garrettson began preaching against slavery and advocating for freedom, which provoked intense opposition, especially in the South. One enraged slave owner came to the house where Garrettson was lodging and swore at him, threatened him and punched him in the face. Garrettson did not retaliate but sought to reason with the man, who finally gave up and left.

Garrettson took his message to North Carolina, where he preached to black audiences and sought to “inculcate the doctrine of freedom in them.” His opposition to slavery was firmly rooted in the gospel and he described a typical meeting with slaves, in which:

Many of their sable faces were bedewed with tears, their withered hands of faith were stretched out, and their precious souls made white in the blood of the Lamb (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 95).

Garrettson also preached to southern white audiences and sought to convince them of the evils of slavery and that God’s will was liberty for all His creatures. In Delaware, Garrettson visited the Stokeley Sturgis Plantation and preached to both the slaves and the Sturgis family. He was able to convince Sturgis that slavery is a sin and Sturgis began making arrangements for his slaves to obtain freedom.

The Methodists Go on the Attack

In 1744, John Wesley (1703–1791) spoke publicly against slavery, declaring that, in God’s sight, blacks and whites are equal and Christ died for all. Many Methodists in America, in both the North and South, picked up on Wesley’s call and became some of the leading abolitionists in America.

James O’Kelly (1735-1826), for example, faced physical attacks because of his bold, excoriating preaching against slavery. He painted slaveholding as a debilitating and demonic kind of sin. It was, he said, “A work of the flesh, assisted by the devil; a mystery of iniquity, that works like witchcraft to darken your understanding, and harden your hearts against conviction.”

Because of the bold preaching of evangelists such as Garrettson and O’Kelly, an anti-slavery movement gained momentum, even in the South. This movement faced intense opposition, as was the case in 1800 when Methodists in South Carolina circulated a petition calling for emancipation. A mob burned the handouts and dragged one of the Methodist preachers through the streets and almost drowned him in a well.

Despite the opposition, the movement for abolition continued to spread, impacting those from all stations and walks of life.

Richard Allen Founds the AME

One of the slaves who obtained his freedom from the Stokeley Sturgis Plantation was Richard Allen. Allen, who had been converted under the preaching of a Methodist preacher while still a slave, became a successful evangelist to both black and white audiences. In 1784, he preached for weeks in Radnor, Pennsylvania, to mostly white audiences and recalled hearing them say, “This man must be a man of God; I have never heard such preaching before” (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 95-96).

Allen became close friends with Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence. As the Awakening waned, the Methodist Church in Philadelphia, of which Allen was a member, decided to segregate the congregation according to race. Allen and other blacks walked out. Rush came to their aid and assisted them in establishing their own congregation. They established Bethel Methodist Church, which became the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) denomination. Allen later wrote:

Dr. Rush did much for us in public by his influence. I hope the name of Dr. Benjamin Rush and Mr. Robert Ralston will never be forgotten among us. They were the two first gentlemen who espoused the cause of the oppressed and aided us in building the house of the Lord for the poor Africans to worship in. Here was the beginning and rise of the first African church in America (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 156).

Paul Strand, senior Washington, D.C. correspondent for the Christian Broadcasting Network, has called Allen “America’s Black Founding Father.”

America’s Founders are Impacted

The spiritual power of the Awakening and the moral arguments it produced against slavery were overwhelming. The pragmatic fruit emerging from the revival include the following:

1) George Washington accepted free blacks into the Revolutionary Army, resulting in one out of every eight soldiers being of African descent. Blacks and whites fought together for freedom from Great Britain.

2) America’s Founders purposely avoided using classifications of race or skin color in the nation’s founding documents. America’s founding documents are colorblind, even if her history has not been. This is why Dr. King, in his “I Have a Dream” speech, could say:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

3) Founders from the North, who had never owned slaves, took new and strong public stands against the institution. John Adams, for example, declared:

“Every measure of prudence . . . ought to be assumed for the eventual total extirpation of slavery from the United States. I have throughout my whole life held the practice of slavery in abhorrence” (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 101).

4) Confronted by the inconsistency of Christian faith with owning slaves, George Washington set in motion a compassionate program to completely disentangle Mount Vernon from slavery. He said:

“I clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union by consolidating it in a common bond of principle” (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 103).

5) As a result of the Awakening, an abolition movement arose and one of America’s Founding Fathers, Benjamin Rush, helped found the nation’s first abolition society in Philadelphia. Rush, a Philadelphia physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence, also exhorted the ministers of America to attack slavery, saying, “While you enforce the duties of ‘tithe and cumin,’ neglect not the weightier laws of justice and humanity. Slavery is a Hydra sin and includes in it every violation of the precepts of the Laws and the Gospels” (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 100-101).

6) Even those Founders who did not free their slaves publicly admitted that it was wrong and sinful and would bring God’s judgment on the nation. It was in the context of the continuance of slavery after the Constitutional Convention that Thomas Jefferson wrote:

God who gave us life, gave us liberty. And can the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are a gift from God? That they are not to be violated but with His wrath? Indeed, I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just and that His justice cannot sleep forever (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 125).

Although it would take a Second Great Awakening (ca. 1800- ca. 1830), a Great Prayer Awakening (1857-1858) and a Civil War (1861-1865) to bring final closure, slavery’s end was sealed in that First Great Awakening that swept Colonial America. It was the Christian Awakening that ended slavery in America.

America is in desperate need of another Christian Awakening. We ought, therefore, to heed the words of Samuel Adams (1722–1803), a passionate abolitionist, signer of the Declaration of Independence and known as “the father of the American Revolution.” While serving as governor of Massachusetts, he proclaimed April 2, 1795, to be a Day of Fasting and Prayer for both Massachusetts and America.

The words of that Proclamation reveal the profound depth of faith in America’s founding generation and shows how they saw their civil liberty tied to their faith in God. It reads in part:

Calling upon the Ministers of the Gospel, of every Denomination, with their respective Congregations, to assemble on that Day, and devoutly implore the Divine forgiveness of our Sins, To pray that the Light of the Gospel, and the rights of Conscience, may be continued to the people of United America; and that his Holy Word may be improved by them, so that the name of God may be exalted, and their own Liberty and Happiness secured (Hyatt, 1726: The Year that Defined America, 104).

This article is derived from Dr. Eddie Hyatt‘s latest book, 1726, available from Amazon and his website at eddiehyatt.com. He is also the founder of the “1726 Project,” whose goal is to spread the message of America’s unique birth out of the First Great Awakening and call on believers everywhere to pray for another Great Awakening across the land.