Senate Judiciary Chair: The People Will Decide Who Picks Scalia’s Replacement

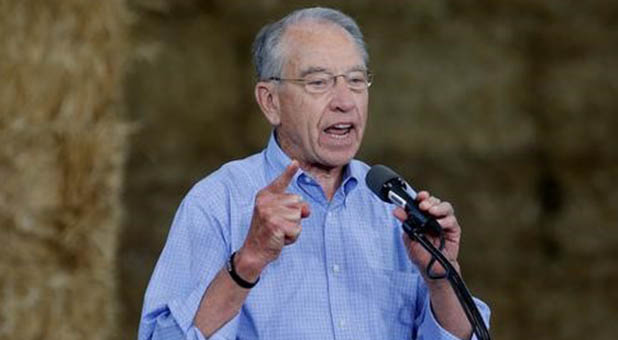

The Senate returned to work from its summer recess this week, and almost immediately, the feud between Minority Leader Harry Reid (D-Nev.) and Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) resumed.

Reid goaded the Senate Republicans over their insistence that the voters would decide who will replace Supreme Court Associate Justice Antonin Scalia. Grassley, however, made it clear Republicans have not changed their position on the matter.

The chairman made a floor speech Thursday in which he said:

The minority leader has again come to the floor to make personal insults and threats, as he tends to do. But political stunts and childish tantrums aside, the minority leader knows that the American people deserve to have their voice heard on the future of the Supreme Court.

We’ve made the decision that the next president will select the next justice of the Supreme Court. We’ve done that because the next justice will have a profound impact on issues that matter to all of us for decades. And we think the People should have a voice in that matter.

I spent the past several weeks meeting with Iowans across my State, discussing the issues that concern them and what’s on their minds looking forward to the election this fall. The vacancy on the Supreme Court created by the death of Justice Scalia came up time and again.

At meeting after meeting this summer, Iowans told me that they appreciate the Senate’s decision that the next president should nominate Justice Scalia’s replacement.

They understand that this nomination will affect the Court for years to come. And for that reason they want to have a voice in the matter. We will give them that voice.

That’s the position that the Judiciary Committee took after Justice Scalia’s death. We wrote to Leader McConnell on Feb. 23 to advise him that the next president should select the next justice.

We explained ourselves this way:

“The presidential election is well underway. … The American people are presented with an exceedingly rare opportunity to decide, in a very real and concrete way, the direction the Court will take over the next generation. We believe the people should have this opportunity.”

Our explanation is all the more true as we find ourselves just two months away from the presidential election this fall. I remain convinced that we owe the people a chance to speak their minds on the Supreme Court in the election.

I’ve not been surprised to hear from Iowans that they want their voices to be heard on this issue. And the Senate’s decision to give the people this chance is no surprise, either. We’re acting in the Senate’s long tradition as a check on the president’s power to nominate.

Take 1968, for example. On June 26 of that presidential election year, President Johnson announced his nomination of Justice Abe Fortas to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court when Chief Justice Warren declared his intention to retire.

Abe Fortas, of course, was already an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, and had been unanimously confirmed by the Senate just a few years earlier. But that confirmation didn’t take place in an election year like 1968.

Within 24 hours of Justice Fortas’s nomination to be Chief Justice, 19 Republican Senators issued the following statement:

“[T]he next Chief Justice should be selected … after the people have expressed themselves in the November elections.”

At the time Democrats held the Senate, so these Members did not control the Judiciary Committee’s proceedings or the Floor. But those 19 Senators promised that if the issue was forced to a vote, they’d “vote against confirming any Supreme Court nominees by the incumbent President.”

These 19 Senators made this commitment—immediately following the President’s announcement of his intended nomination—for the same reasons the Judiciary Committee has elected not to move forward the President’s nomination of a successor to Justice Scalia.

Here’s what Senator Howard Baker had to say about it:

“I have no questions concerning the legal capability of Justice Fortas … [but] there are, in my opinion, more important considerations at this time.”

He continued:

“The appointment of the Chief Justice really ought to be the prerogative of the new administration. … In my opinion, the judicial branch is not an isolated branch of Government … it is and must be responsive to the sentiment of the people of the nation.”

Those are my thoughts exactly.

And they’re not just shared by Republicans. Recall of course that then-Chairman Biden said in 1992 that processing a Supreme Court nomination in an election year harms the nominee, the country, and the Senate. And he only spoke of coming together on a nominee in the next Congress with a new president.

I’d finally like to address one more argument I’ve heard recently from those who support the president’s nomination this election year. As we’ve drawn closer and closer to this presidential election, they’ve tried to use the length of this vacancy as reason to move forward with this president’s nomination. I’ve even heard some say that this is the longest Supreme Court vacancy ever. That’s just false.

I’ll list just a few examples: Two vacancies—to fill the seats of Justices Baldwin and Daniel—lasted longer than two years in the 1800s. Six Supreme Court vacancies have lasted longer than a year and two more have lasted nearly that long.

As this election draws closer by the day, the Judiciary Committee’s position remains consistent. The next president will choose Justice Scalia’s replacement.

Senators have made this choice before—like the 19 who declared during the 1968 election year that the next president should choose Chief Justice Warren’s replacement. They did so, just as then-Chairman Biden said, because that course was best for the country during a politically-charged election year. The same thing is true this election year—the next president will select the next Supreme Court justice.

I yield the floor.