The Electoral College Must Endure

Some supporters of Hillary Clinton are taking out their frustrations in a vigorous campaign to, as they say, “abolish the Electoral College.” Their mantra is that since Clinton had a larger share of the popular vote than Donald Trump, she effectively won the election. Democrat Senator Barbara Boxer reflects this view: “The Electoral College is an outdated undemocratic system that does not reflect our modern society and it needs to change immediately,” says Boxer. In its place, Senator Boxer wants a popularly elected president.

This means, of course, that all governmental office-holders would be elected by a direct vote. Actually, the word “democracy” does not appear in the Constitution or in the Declaration of Independence. Neither are all office-holders elected. James Madison summed up the reason the founders opposed all office-holders being directly elected in Federalist No. 10, observing that in democracies there is no check on the majority faction to protect the rights and interest of the minority. Elsewhere, he expressed concern about “mob rule” in democracies.

The founders came up with another idea. But, before we turn to that, let’s illustrate how the direct vote system, desired by Boxer, would work out. Think about a hypothetical 2016 presidential election.

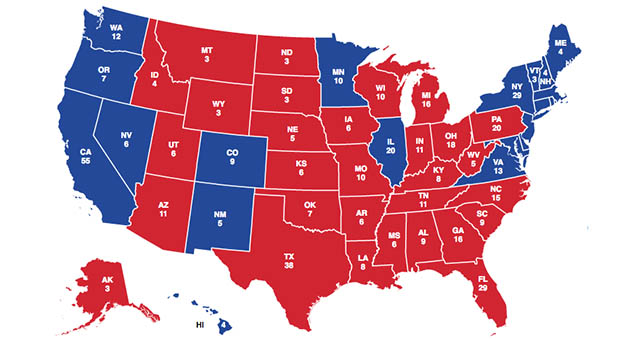

The present population of the nation is about 320,000,000 people. Assume that half of them are eligible to vote—160,000,000. Probably only half of that number would actually vote (80 million). Then 40,000,001 people could elect the president. Stated another way, about 25 percent of eligible voters could elect the president. That would mean only a few states with large populations—California (40 million), Texas (27 million), Florida (20 million) and New York (20 million) could elect the president. Specifically, California alone could elect the president. This would mean the fly-over states would have diminished power.

It’s obvious in a direct-vote system (i.e., direct democracy) one party, or faction as the founders called them, could have most of the power. And, the obvious must also be stated: The rest of the states would have little or no effective power. Members of the Constitutional Convention recognized this imbalance of power among the states and that it would likely cause perpetual unrest in the nation. Thus, the founders sketched out something new, something unique, in the Constitution of 1787—namely, a federal republic.That republic has been affirmed for decades by millions of Americans every day when they recite, “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the republic for which it stands….” Though not emphasized in textbooks and by teachers in today’s public schools, evidence of it is overwhelming.

Consider what the Constitution itself says. Article IV, Section 4 states: “The United States shall guarantee to every state in this Union a republican form of government.” To the founders, this meant a rejection of monarchy and heredity rule. In place of that, Madison wrote famously in The Federalist Papers (No. 39) that a republic has a government which derives all of its powers “directly or indirectly from the great body of the people.” And he said, its powers are administered by people holding their offices for a limited time and during good behavior. Moreover, suspicious of concentrated powers, as in the British monarchy or Parliament, the founders also embraced French thinker Baron Montesquieu’s idea of a separation of powers in the government, expressed in his “Spirit of the Laws.” The result was the familiar three branches of government—executive, legislative and judicial. As Madison and others envisioned, when each branch had its own basic power, it could be used to check excesses that might emerge in the other branches of the government.

Significantly, the founders decided that as part of the republican system of government, it would be prudent to use “electors” in the indirect election of the president and vice president. This little-understood concept occupies much space in the Constitution and its Amendments. Together, the Constitution and the Amendments have 7,591 words. Comments on the use of electors take up between 2,500 and 3,000 words—many more words than any other topic. Readers can find most of the comment on “electors” in the following places: Article II, Section 1(1789); in Amendment XII, (1804); in Amendment XX (1933) and in Amendment XXII (1957).

Readers of the Constitution might be surprised to see that the term “electoral college” does not appear anywhere in the Constitution or the Amendments. In fact, it first appeared in discussions in 1845. Eventually, it was codified (1948) in 3 US Code. Extensive provisions for electors in the American governmental system’s executive branch testify to its importance as a part of the republic the Constitution created.

It’s fair to say that without the electoral system the republic would dissolve. On reflection, Americans should recognize the crucial place the electoral system has in the republic. It must endure.

Dr. L. John Van Til is a fellow for humanities, faith and culture with The Center for Vision & Values at Grove City College. His latest books are Thinking Cal Coolidge and The Soul of Grove City College: A Personal View.

This article was originally published at VisionAndValues.org. Used with permission.