Some Russian and American Christians—fearful of returning to a time when underground churches were the norm and publicly speaking the name Jesus Christ a crime with children present—remain in the dark now that President Vladimir Putin has signed into law new regulations on religious activity.

Christian media in the United States published news reports about the Russian law this summer but, depending on the source, the information either elevated or alleviated worries of a return to Soviet-era days when believers in Jesus met in secret, out of view of communist spies.

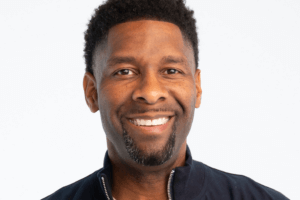

Sergey Achkasov, a Russian who loves Jesus Christ and His teachings, was on vacation in the U.S. this summer when the Kremlin and Putin passed the law, which became effective July 20.

A former pastor and church planter in Russia, Achkasov’s interest in the edict is personal: His brother is a worship leader and missions director in Russia, whose registered congregation must obey the law or pay fines for violations of what’s also billed a counterterrorism measure.

Even more personal for Achkasov are the memories of Soviet-era persecution of Christians, including himself: He was beaten between the ages of 6 to 9 for talking about God at home and at the elite Soviet school where he studied piano more than a decade before communism’s fall in 1991.

So in his free time, Achkasov began to study the law online from a summer vacation home close to the Rocky Mountains in Colorado, where he and wife, Jill Achkasova (female surnames add an “a” in the Russian language), spent the month of July.

“Somebody got the idea that every conversation about God or spiritual things is against the law. It does give definition to what is and is not missionary activity,” says Achkasov, adding that the law’s major target is potential terrorist activity in Russia, where Orthodox, Protestant and Islamic faiths exist.

Much of the law addresses issues of electronic surveillance and storage of phone records as a counterterrorism measure.

“A church is not forbidden to conduct missionary activity under this law but it does need to be a legal, registered church—not underground like some from the Soviet era,” says Achkasov, who was baptized in the Russian Orthodox Church but attended illegal and legal Baptist, Pentecostal, charismatic and Catholic congregations on a youthful quest for God.

“The law is a last-ditch effort to get churches registered and to prevent large-group gatherings where the potential for terrorism exists,” he says.

The law doesn’t forbid one-on-one dialogue about God, private prayer in homes, or personal evangelism as some reports have stated.

The proof: Achkasov says he will continue to speak about Jesus Christ with citizens on Moscow’s streets—if and when people are willing and interested in hearing him—without fear of persecution by Russian authorities.

The irony of Achkasov’s message—a tale of his face-to-face encounter with Jesus—is that it hearkens back to the Soviet era, when repression was real and spiritual conversations with children forbidden.

“I saw Jesus Christ when I was 9 years old,” Achkasov says as Jill Achkasova nods, just as she does every time her husband tells the story.

“It was the thing that strengthened my faith as a child when everybody and everything was against me,” he says.

When Achkasov was 18, his parents gave him an ultimatum: Renounce God or move out. He left, living with Christian friends for a short time. Shocked by her son’s steadfastness, Achkasov’s mother called the home where her son was staying, imploring him: “Go to your meetings. Read your Bible. Only come home.”

It’s a story Achkasov has told innumerable times in private and at public concerts with his wife—who accompanies him musically with a violin and speaks Russian she learned at college in the U.S.—speech that’s protected by the new law, as is Achkasov’s recorded music, a CD titled “Fire of the Holy Spirit.”

“My impression is that the church in America is more restricted than in Russia because it’s here in America that it’s illegal to speak about God. In Russia, priests go to schools and teach children about God, and the stories of Easter and Christmas are broadcast on loud speakers for people outside of churches to hear,” Achkasov says.

Current conditions in America, where prayer in school is banned and talk about God shunned, remind Achkasov of the Soviet Union of his formative years, characterized by both fears and tears.

Today the 46-year-old Achkasov harbors painful memories of whippings and tongue lashings that followed his talk about God at home and school.

A good communist, Achkasov was told by his mother, doesn’t believe in God, especially one who’s expected to represent his country’s ideals abroad. Even before his birth in 1970, Achkasov’s destiny was determined by his parents, who purchased the piano he learned to play through his studies at the Russian Conservatory.

“This was a child who was like the prophet Jeremiah, who said that ‘His word was in my heart, as a burning fire shut up in my bones,'” says Jill Achkasova, whose journey with Jesus began in the Foursquare Church in America. She met Sergey at the Russian Orthodox Church where he was the organist at the time. They later married.

A short-wave radio, also a gift from unbelieving parents, only increased the 8-year-old’s interest in God and the Bible after young Sergey discovered a gospel program broadcast by Russian-speaking evangelist Earl Poysti.

Beyond curiosity about a God he was told didn’t exist, Achkasov activated his budding faith by sharing Poysti’s Bible messages, writing them word for word on paper, then hand-delivering them to his Soviet neighbors’ mailboxes.

Almost 40 years later, Achkasov met his spiritual father on one of a handful of trips to Colorado.

“I just wanted to share. (Poysti’s broadcasts) touched my heart and I wanted people to know,” says Achkasov, who also sought out priests within the Russian Orthodox Church with questions about God at the same time.

Because the priests were forbidden by Soviets officials from speaking to children, Achkasov turned to an underground Baptist church where members clandestinely shared single pages of the Bible in an apartment.

Another Baptist church, this one registered with the government, had quick access to complete copies of the Bible, whetting further Achkasov’s spiritual appetite for God and his Word.

Shortly after Achkasov accompanied his mother on a business trip to Estonia and, as was his bent, he ended up in a church: This one a Pentecostal/charismatic congregation where Achkasov heard discussion of topics he’d read about but didn’t fully understand.

Spiritual gifts, including tongues in particular, intrigued Achkasov as church members explained them. He determined he would later kneel and pray to receive his heavenly language but, stepping off the bus, unknown words poured over his lips. A practice he continues today.

In his 20s and after the Soviet Union’s dissolution on Aug. 1, 1991, Achkasov planted seven churches, worked alongside a group that started 20 congregations total, and served as pastor himself during the ’90s.

Today the churches Achkasov pioneered are still preaching the gospel as independent, self-supporting bodies with pastors who are capable of dealing with challenges, if any, associated with the new law.

“This means that I fulfilled my roles as pastor and church planter. I did what I was inspired to do at the time,” he says.

Achkasov’s brother, 41-year-old Vladislav, is a leader at a Pentecostal/charismatic church, but because it’s recognized by Russia, its members can get permits to legally preach the gospel in public.

The two brothers discussed the matter by telephone within days of a signature by Putin, who attends the Orthodox church.

“There’s no fresh news of any actions on the part of the government directed against churches,” Vladislav Achkasov says. “The law seems mostly directed at terrorists that preach radical Islam, not at Christian missionaries and churches,” he says.

Vladislav’s church is challenged with finding a permanent home, and some of its members are prevented from attending because of transportation or other issues. For some, it’s been a crisis of faith, but nobody in his church is currently affected by the law, adversely.

“If we were all on fire and preaching the Gospel actively like we used to, then possibly a law would have more of an effect on us. We really need some kind of revival,” Vladislav says.

A leader of the main evangelical body, which includes Pentecostals and charismatics in Russia, advises Putin. The president reportedly says he understands the fears of some Christians.

“Sergei Ryakhovsky, the head of the large Pentecostal/charismatic movement I was a part of, saw the panic among the churches and wrote President Putin, asking him to not sign the law.

“Putin answered in a letter, stating that the law doesn’t contradict the article of the constitution that guarantees freedom of religion for all citizens,” Sergey Achkasov says.

Real suppression during the Soviet era—not the mere fear of it associated with the new Russian law—is something Achkasov discussed in an emotional and dramatic meeting with his spiritual father, Poysti.

“I started listening to your radio show when I was 8 years old,” Achkasov told a teary-eyed Poysti, a broadcast minister with Russian Christian Radio during his lifetime.

“Everybody around me would beat me when I mentioned God. Your ministry opened the world of Christ to me, and it really helped me to understand the Bible.

“I’m the fruit of your ministry,” Achkasov said, hugging his spiritual father, who was born in Russia and became a citizen of Sweden and the U.S.

A few years later, in 2010, Poysti died in Estes Park, Colorado.

Achkasov’s biological father, an atheist during the Soviet era, repented of his unbelief, confessing his faith in God before he died. The mother who beat her son for talking about God shares the same faith today.

“He is my pastor today,” says Jill Achkasova, who was baptized in the Foursquare Church and is a member of the Russian Orthodox Church, where she met Sergey. “He retains a pastor’s heart even though he’s no longer a pastor.”

See an error in this article?

To contact us or to submit an article