What ‘The New Yorker’ Got Right and Wrong About Racism in the White American Church

Although Michael Luo’s article in The New Yorker came out Sept. 2, I didn’t see it until a childhood friend, himself a liberal Jewish Democrat, sent it to me. It is entitled “American Christianity’s White-Supremacy Problem,” and it raises some very serious concerns. What did Luo get right and what did he get wrong?

Luo begins his article with a disturbing anecdote from the life of Frederick Douglass while still a slave. When his master became a Christian, rather than making him “more kind and humane,” as Douglass had hoped, the reverse was true. Douglass wrote, “If it had any effect on his character, it made him more cruel and hateful in all his ways.”

Worse still, Douglass’ master justified his cruel behavior with verses from the Bible, making his Christian profession all the more abhorrent.

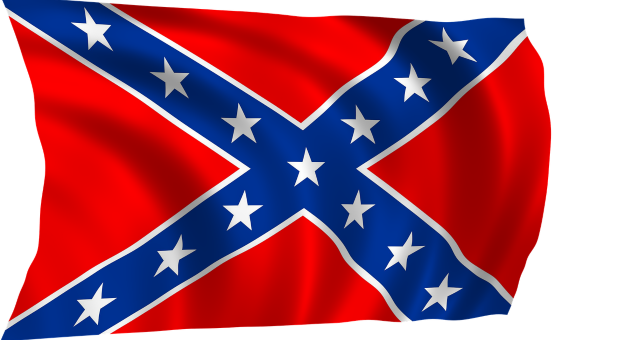

But, Luo notes, this is not just a 19th-century problem for white Christians. Rather, Luo informs us, “In a 2019 nationwide survey, 86% of white evangelical Protestants and 70% of both white mainline Protestants and white Catholics said that the ‘Confederate flag is more a symbol of Southern pride than of racism’; nearly two-thirds of white Christians overall said that killings of African American men by the police are isolated incidents rather than part of a broader pattern of mistreatment; and more than 6 in 10 white Christians disagreed with the statement that ‘generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for Blacks to work their way out of the lower class.'”

To be sure, there are certainly some Americans for whom the Confederate flag is a symbol of Southern pride rather than racism. (Not being from the South myself, those feelings are quite foreign to me.) And there are many people of conscience who, based on the data they have reviewed, believe that African American men are not specifically singled out for killing by the police. But I find it difficult to imagine how “more than 6 in 10 white Christians” deny what is to me a self-evident statement: namely, “that ‘generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for Blacks to work their way out of the lower class.'”

These sentiments are backed up by the much-discussed recent book by Robert P. Jones, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity, which Luo references. And they are given historical context in the important book by Jemar Tisby, The Color of Compromise: The Truth About the American Church’s Complicity in Racism, also referenced by Luo.

To the extent Luo reminds us of the past failings and blind spots of the American church, he does well. And to the extent those blind spots exist, he does well to draw our attention to them as well.

Yet there are some clear misses in his article.

First, he notes that, “In surveys that measure how warmly people say they feel about Black people, the sentiments of white evangelical Protestants exceed those of the general population. (Other white Christians’ responses fall close to the mean.) Yet the vast majority of white Christians remain indifferent to the symbols of white supremacy and skeptical of the realities of racial inequality.”

What, then, does this tell us? Perhaps these white evangelical Protestants really do have hearts of love. Perhaps they really do believe in racial reconciliation. Perhaps they really do want to right wrongs when they become aware of them. And perhaps these alleged “symbols of white supremacy” have no such meaning to them, which is why they are indifferent to them. And perhaps they are unaware of some aspects of racial inequality.

This is a far cry from a white Christian master mistreating a Black slave in the name of Christianity, quoting the Bible as he mercilessly lashed his purchased possession.

Yet it does remind us of the importance of honest and ongoing dialogue. If there are insensitivities on the part of sincere white Christians, then when they become aware, they will become sensitive. Let us continue to talk together across racial and ethnic lines.

Second, Luo repeats some the standard mischaracterizations about President Trump and his supporters, portraying him as a racist followed by white Christian racists for whom “Christian nationalism” means a white America.

Accordingly, Luo points to Trump’s alleged “reluctance to condemn white-nationalist protesters in Charlottesville, and his scapegoating of China for the coronavirus pandemic.”

In point of fact, as has been pointed out endlessly since Charlottesville, Trump immediately condemned the white nationalist protesters on the day of the event, making an even stronger statement in a subsequent news conference. And his “scapegoating” of China—which many would argue is not “scapegoating” at all—is hardly race-based. Had the virus allegedly been manufactured and/or released by, say, an anti-America Canadian government, Trump would have labeled it the Canada virus (or something even more biting).

As for Christians shouting “MAGA,” I’m sure that some of them are racists who dream of a white America. But the vast majority of those I have interacted with have issues with the left, not with Blacks; with morality, not color. Luo fails to factor this in adequately.

Third, Luo faults abolitionists like Charles Finney in the 1800s and anti-segregationists like Billy Graham in the 1900s for putting soul winning ahead of fighting racism.

To be sure Luo does not castigate these leaders for their stances. And he mentions that Martin Luther King, Jr. advised Graham to keep his focus on gospel preaching. But he fails to recognize that these are biblically based, socially sound principles. We preach Jesus and repentance first, and that leads directly to godly social action.

Finney, for his part, predicted a national bloodbath if abolitionism were put first and revivalism put second. He knew that without a massive change of hearts on a national level, a costly civil war would ensue.

Perhaps the war was inevitable. But Finney’s method was to change society by changing hearts, while at the same time aggressively opposing slavery. (For a contemporary application of this principle, see “Flipping the Courts and Turning the Hearts.”)

Graham held to a similar strategy, knowing that his primary calling and gifting was that of an evangelist, while also understanding that true Christian dedication would result in the end of segregation. Luo sees this as a deficiency, as if Finney and Graham fell short of their callings, which is certainly not true.

And it is misses like this that undermine Luo’s bombastic closing statement. He wrote, “Today’s ‘slave-holding religion’ is preached on Fox News, conservative talk radio and the rest of the right-wing media ecosystem; they daily bear false witness. Jesus’ blessing for peacemakers may demand that Christians confront these institutions of demagoguery and division in the name of the kingdom.”

Had he been more nuanced and accurate, seeking to understand those whom he attempts to expose, his article would have been much more constructive. As it is, his exaggerations and misstatements detract from the important issues he does address. {eoa}